MANUSCRIPT

Richard C. Beacham

The Future of the Past: New Developments in Computer-Based Cultural Heritage Research

Introduction

I might even show you my photograph album. You might even see a face in it that might remind you of your own of what your once were. You might see faces of others in shadow or cheeks of others turning or jaws or backs of necks or eyes, dark under hat, which might remind you of others whom you once knew, whom you thought long dead but from whom you will still receive a sidelong glance if you can face the good ghost. Allow the love of the good ghost. They possess all that emotion trapped. Bow to it. It will assuredly never release them but who knows what relief it may give to them. (from Harold Pinter, No Man's Land)

The past, including of course cultural heritage, is composed of things both material and, for want of a better word, "ghostly": memory, imagination, the "mind's eye", even as Pinter suggests, "emotion trapped". In attempting to access and "release" to our understanding that material and immaterial past - that heritage - from earliest times we human beings have employed as one of our most evocative tools visualisation, through which we try to make the vanished past, the no longer seen, and even sometimes that which was never seen, visible to our perception and contemplation.

Still images are intrinsically static and time bound; they can acquire their projection into space and extension into time only by virtue either of imagination or what might be termed re-enactments, or embodiments. For example, theatrical performance (history plays) or physical representation (pageants, or statuary). Sometimes such representation has been used to breathe "virtual" life back into the dead, while evoking their lives and their meaning to a culture. The ancient Romans for example (a society obsessed with the visual if ever there was one), at the public funerals of prominent men not only employed actors wearing the mask and clothes of the deceased to depict them as if physically present at the funeral, but also had actors - sometimes hundreds of them - similarly represent all of the family's deceased ancestors in generations past. The funeral thus comprised a vast congregation of the living gathered together and a convocation of the dead summoned up both physically and imaginatively (mind and matter) to represent the past. "When the masked impersonators reach the rostra, they all sit in a row on ivory chairs. There could not be a more inspiring vision…for who would not be moved by the sight of the images of men renowned for their excellence, all together as if alive and breathing? What spectacle could be more glorious than this?...The celebrity of those who performed noble deeds is rendered immortal, while the fame of those who did good service to their country becomes known to the people and a heritage to future generations" (Polybius 6.53).

But as Shakespeare noted, "These our actors, as I foretold you, were all spirits and are melted into air, into thin air".

The advent and advance of computer-based visualisation technologies have extended our capacity to evoke and "hold" the "baseless fabric of this vision"; the appearance and with it the emotion and "feel" of the past. Photography gave us accurate images, and their capacity to show people and places in a series of views spanning a great sweep of time - even entire lifetimes - powerfully evoked in the mind's eye the passage of time, even though they are themselves static and time bound.

The invention of the phonograph and sound recording captured sound in its native dimension (essential to its very existence) of time itself. They thus allowed us to hear the voices of the past - those operatic arias for example, of long-departed artists, not only summoning up for us once again the emotion of the songs themselves, but because the voices that re-render them for us now, are long dead, moving us with even greater poignancy and intensity of feeling.

Then, the cinema brought sight, sound, movement and time together in powerful synthesis, to capture and hold what previously we could only imagine or re-enact as a transient performance or spectacle, what Shakespeare called an "insubstantial pageant faded".

In recent decades, computer-based visualisation technologies have extended still further our capacity to conjure the past and its heritage. They do so not only because they can with ever-increasing power evoke the essential elements of sight, sound, space, and - through movement in space - time, but most potently of all, because they can suggest, to our minds' eyes, our own immediate presence in the past, through our capacity to interact with virtual environments. The advent of avatars has of course given such interaction the additional stimulus of mentally evoked bodily awareness. By doing this, computers have vastly extended our capacity to visualise, hear, perceive, spatially explore and, through virtual empathy, "feel" past environments.

This is not merely an extension of awareness and understanding: it offers as well a greatly expanded capacity to carry out research and acquire new forms of knowledge that were previously unattainable, the potential of which we are only now on the threshold of exploring. I want in the remainder of this paper briefly to survey a few selected examples of merely some of the research areas and evocative historical presences that virtual technologies have opened up to us and which my own research group, The King's College Visualisation Lab, is currently investigating.

The Visualisation team that is now King's Visualisation Lab began in 1996 at the University of Warwick with my hiring a single Research Assistant. Now at King's College London, the team comprises two theatre historians - myself and Hugh Denard, both of us specialising in ancient Greek and Roman theatre history; Senior Research Fellows, Martin Blazeby and Drew Baker, who are responsible for most of the computer modelling we do; New Media Artist, Michael Takeo Magruder; and Research Fellows, Anna Bentkowska-Kafel and Marco Bani, who support and contribute to our work in a variety of crucial ways.

Theatron 3 in Second Life

In 2002, when still located at the University of Warwick, we led a six-partner international consortium, which completed and launched the Theatron Project, funded under the EU Telematics in Education, Training, and Research Programme. This online interactive educational module comprised digital 3D models of twenty major, historic European Theatres, from the 5th-century BC Theatre of Dionysus at Athens, to the 20th-century Schaubuhne am Lehniner Platz in Berlin (http://www.theatron.org).

Each was meticulously researched by subject experts, modelled following rigorous standards of architectural and archaeological accuracy, and contextualised with a vast array of graphic and textual materials. Each site was represented by both a simple, real-time navigable model in VRML and a collection of pre-rendered images and animations of highly detailed models created using 3D Studio Max.

Users of this original Theatron site can study the critical analyses of the spaces provided, but can also independently assess the evidence on which the 3D reconstructions are based (letters, critical descriptions, architectural texts, sketches, drawings and paintings etc.). The application was unprecedented as an ICT learning tool for higher education, and widely acclaimed, winning a 21st-century achievement award as Laureate in the Computerworld Honors Program and was the subject of several case studies in the EU Digicult Technology Watch Reports.

Now KVL is recreating the entire Theatron module within the Second Life platform. The result is an interactive teaching and learning resource that takes full advantage of the pedagogical potential of a real-time, avatar-based, multi-user environment.

Second Life not only allows real-time navigation to be combined with relatively high graphical quality, but also, replacing the disembodied eye of Theatron 1 with the avatar, transforms the theatres from objects to manipulate into imaginatively immersive spaces to inhabit, singly or socially. Scripts supplement the models with rich, interactive content, such as props, sound effects, lighting and scenic technologies, streaming video, and a Director Tool helps users to coordinate virtual rehearsals and performances incorporating individual and group actions and choreography. Pilot projects with academics and students from a wide range of disciplines in five UK Universities are under way, including creative writing, scene design, theatre history and mixed reality performance.

Theatron 3: The Theatre at Epidavros in Second Life. Model by Drew Baker and BetaTechnologies. © KCL 2009

We are also developing shared heritage projects and teaching curricula with the University of Pisa's degree programme on Digital Humanities, focused around a shared Island in Second Life called Digital Humanities Island, to which we also invite members of the international Digital Humanities community to avail themselves of our centre, Arketipo, for virtual and mixed reality events such as meetings, classes, workshops and conferences.

Roman Theatres at Pompeii: Visualisation and Virtual Performance

Following a major, international study of the Theatre of Pompey in Rome (http://www.pompey.cch.kcl.ac.uk/index.htm), for the past two summers (2007 and 2008) KVL with grant support from the British Academy, has been working with an archaeological survey team from the University of Melbourne, led by the leading Roman theatre authority Prof. Frank Sear. As part of this work we have prepared the first comprehensive plans as well as the first detailed 3D computer models of these extraordinary important heritage sites.

Artefact, digital scan, rapid prototype, finished mask with actor. Model by Martin Blazeby. Mask making by Malcolm Knight. © King's College London 2009

At the same time, supported by a substantial grant from the British Arts and Humanities Research Council, we are currently combining this architecturally-focussed work with the recreation of masked performance, to demonstrate how these theatres might have functioned as venues for seeing and experiencing living works of art (http://www.kvl.cch.kcl.ac.uk/masks/). In collaboration with the Universities of Durham, Southampton and University College London, the Project has prepared three-dimensional scans of selected ancient mask miniatures, including those of Roman periods and of tragedy, and has then created by 3D printing a number of artefact-size replicas and in turn, with Malcolm Knight of the Scottish Mask and Puppet Centre, has prepared full-size masks from these in order to conduct practice-based research with living performers.

Noh actor, Akira Matsui in Gypsy MoCap Suit (left) and Commedia dell'arte actors performing in HD ChromaKey studio (right) © King's College London 2009

The team has also conducted 3D motion capture and ChromaKey video recording involving practitioners from different world masked-performance traditions, including from the Noh tradition with Akira Matsui.

Commedia dell'arte actors perform a scene from a Roman comedy, inserted, by ChromaKey, into the Odeion at Pompeii. Model by Martin Blazeby. © King's College London 2009

It has then situated the resulting data in KVL's models of ancient theatre spaces, including those at Pompeii, and has investigated the results for their significance for theatre studies and for wider research communities.

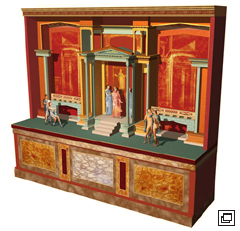

On the rear wall of this model of the Odeion at Pompeii by Martin Blazeby is a fresco in the "Second Pompeian Style". Traces of such a Second-Style fresco were found on the rear wall of the Odeion, but not enough to reconstitute the entire design. However, the 1st-century author, Vitruvius, whose treatise "On Architecture" remains a cornerstone of the Western architectural tradition, tells us that Roman houses were decorated with frescoes that were sometimes "in the style of" painted theatre facades (7.5,2). Of all the many Roman "theatrical" frescoes that have survived, this one from a Villa in nearby Oplontis provides the best clues to what such a large-scale, theatre facade might have been like in this period.

Prompted by our interest in not only the theatres, but also the pervasive, theatrical culture of ancient Rome - the subject of a forthcoming book for Yale Press by Hugh Denard and me: Living Theatre: Roman Theatricalism in the Domestic Sphere - we undertook a Leverhulme Trust-sponsored study of numerous "theatrical" frescoes, both to understand what they might have signified to Roman viewers, and see what clues they might give us as to the style of actual stage architecture and scene painting: http://www.skenographia.cch.kcl.ac.uk/.

The project involved conducting detailed, measured perspectival analyses and making interpretative decisions where details are either unclear or, due to Escher-like optical games, deliberately ambivalent.

Visualisation derived from a fresco design from the House of Pinarius Cerialis, Pompeii. Model by Martin Blazeby. © King's College London 2009

While our own modelling process has greatly furthered our own understanding, if we want other scholars to be able to understand and, more importantly, evaluate what we have done, we need clearly to show not only the finished images, but also the process of interpretation, with all the decisions made along the way, and how each decision affected the final outcome. We all do this in print as a matter of course - explaining the logic of our arguments and, through footnotes and bibliographies, showing their relationships to other arguments and intellectual contexts. However, there is not, in the historical or cultural heritage domains, a ready-made set of conventions for making "intellectually transparent" the logical progression of visually-constructed arguments. In order to render visualisation outputs academically valid, intellectually transparent, susceptible to critical assessment, one must publish not only the finished product, but also documentation of the process of visualisation - a type of information we term "paradata".

The most significant breakthrough in this respect has been the publication of The London Charter for the Computer-based Visualisation of Cultural Heritage, which established the core principles that should inform serious heritage visualisation efforts. The first official draft of the Charter, published in June 2006, is available on the London Charter website: www.londoncharter.org in English, Italian, Japanese and Spanish versions, has had a significant impact on the evolution of heritage visualisation policy at national and international levels, and is central to a forthcoming book edited by Drew Baker, Anna Bentkowska-Kafel and Hugh Denard entitled Paradata: Intellectual Transparency in Historical Visualization (Ashgate). The most recent draft of the London Charter (2.1, February 2009) sets out six principles, on Implementation, Aims and Methods, Research Sources, Documentation, Sustainability and Access.

Thus, the Skenographia project website includes a project-level description of the methodology we used, and each study then has a detailed, step-by-step description of how the methodology was applied, covering the nature of the interpretative challenges posed by the artefact in question, the key methodological and interpretative decisions made, and how these relate to the conclusions at which the study arrived.

Roman Villas

Our research gave us a keen understanding not only of the role visualisation can play in the documentation and preservation of vulnerable, tangible, cultural heritage, but also of the importance of viewing such Roman frescoes as those explored in the Skenographia project as fundamentally spatial, rather than pictorial compositions, conceived as playful interactions with both their actual architectural settings and the furnishings and human presences near them. Determined to investigate these possibilities and properties further, we have begun a series of projects to develop populated, real-time models of entire, Roman houses and villas.

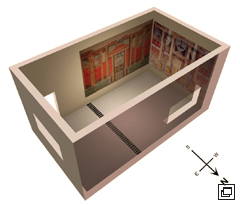

Room 23, Roman Villa at Oplontis on a plan by J. Stanton Abbott. 3D visualisation by Martin Blazeby. © KCL 2009

The Roman Villa at Oplontis, near Pompeii, which was excavated from 1964 through the early eighties, is, in size, architectural layout and the range and quality of its paintings and mosaics, arguably the most important Roman Villa ever to come to light. John Clark, University of Texas, in collaboration with the Superintendancy of Pompeii and KVL, is leading the first scientific survey and comprehensive publication of the villa.

As part of this effort, KVL, with funding from the Leverhulme Trust, is creating digital models of the entire villa both to document its existing state and also to attempt reconstructions of its lost, superseded and damaged elements.

The models derive their measurements from a Total Station survey of the site, and their textures from extensive existing archival, as well as new, photographs. The models will be available online, navigable in real-time, and will link, by hotspots, to datasets comprising archaeological finds, landscaping, images, and a complete, wall-by-wall inventory of the villa's frescoes.

At least one version of the model will be created in an avatar-based, multi-user environment, allowing the team hypothetically to recreate domestic architecture, inhabitants, lighting conditions and furnishings, while allowing users to experience the impact of the entire villa's configuration as it unfolds upon viewers moving through space. In accordance with the London Charter, the project will allow users to see distinctions between fact and hypothesis.

Room G, Villa at Boscoreale, showing digitally-restored frescoes and mosaic. Model by Martin Blazeby. © KCL 2009

Just last month, KVL agreed a new project with the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, focussed upon another Roman Villa from the Bay of Naples area, at Boscoreale. This project will produce a detailed three-dimensional computer model of the known architecture and decor of the Villa which was excavated at the end of the 19th century. The Villa's paintings were detached from the walls and dispersed through auction in 1903 into many museums around the world, while the Villa itself was re-buried, and remains to this day inaccessible. The mind's eye might evoke the Villa's presence, but physical reunification of the surviving fragments is impossible. This project will therefore visually reunite the Villa's frescoes and mosaics, and virtually restore them to their original architectural settings.

Doing so will significantly extend our understanding of the site. Photographs both of the Metropolitan Museum's own extensive collection of frescoes from the Villa and of the other paintings dispersed in some ten museums in Europe and America, will be augmented with line drawings of lost elements derived from Barnabei's original publication of the Villa (Rome, 1901). The Project will identify and correct some erroneous fresco restorations as well as misleading aspects of the Museum's isometric Projection of the Villa which, despite certain shortcomings, until now has been the standard reference for the scaling and location of the Villa's decorative elements.

Finally, we hope to undertake a similar Project focussed upon Nero's great and notorious "Golden House", the Domus Aurea, in Rome. This will be a collaborative Project between KVL, Rome based European partners, and a research team from the Departments of Art History and Classics at Emory University, Atlanta led by Prof. Eric Vaner, which is preparing a critical commentary and critical investigation based upon the accounts of Nero's life in Suetonius, Tacitus, and Dio Cassius.

Digital restoration of Chief Banqueting Room, Domus Aurea Neronis. Model by Borghini and Carlani. © Borghini and Carlani 2008

The Domus Aurea is the quintessential monument, expressing in space, architecture and decoration, Nero as man and emperor. A self-contained city within the city of Rome, it comprised not only unprecedentedly sumptuous rooms and attenuated porticoes, marvels of mechanical ingenuity and a lake "like a sea", but also "corn fields, vineyards, pastures, and woods, containing a vast number of animals of various kinds, both wild and tame." It is, in some senses, the built analogue to the ancient historians' texts and the new Commentary will afford, for the first time, interpretations of each systematically to inform the other.

The initial phase of the project will be to complete the suite of dining rooms described by Suetonius:

The supper rooms were vaulted, and compartments of the ceilings, inlaid with ivory, were made to revolve, and scatter flowers; while they contained pipes which shed unguents upon the guests. The chief banqueting room was circular, and revolved perpetually, night and day, in imitation of the motion of the celestial bodies.

KVL and Emory will work with two European partners, Raffaele Carlani and Stefano Borghini, currently working for the City of Rome on historical analysis and visualisation of the Ara Pacis. Some years ago, Carlani and Borghini, created, for their doctoral research at the University of Rome, what still remains the most highly detailed, meticulously researched and documented three-dimensional computer model of the known architecture and decor of the Nero's Golden House.

KVL will derive an interactive, real-time-navigable, digital model of Carlani's and Borghini's models in an online, multi-user environment, again linked to the research sources and scholarly documentation required to make the visualisations "intellectually transparent."

Mixed Realities: The Vitruvian World and Rhythmic Space(s)

Thus far, I have discussed projects that demonstrate how computer-based visualisation technologies are potent impacting upon the way we conceive and conduct various strands of historical research. I wish to conclude, however, with two projects which give some sense of how dramatically these adventures in sight, sound, space, movement, time, presence and bodily awareness are re-weaving the fabric of our vision of how we might engage with both the historical past and our own contemporary culture.

The first is a complex, multi-dimensional, artwork that emerged out of a highly technical, historical study. Some years ago, my colleague Drew Baker started to investigate Vitruvius's prescriptions for temple architecture, creating an algorithm derived from Vitruvius' formulae, that would automatically construct, as a three-dimensional digital model, any type, style or scale of temple that the user might request. Then, in 2007, he and our artist colleague, Michael Takeo Magruder, created a new version of this "Ideal Vitruvian Temple" within Second Life, but re-envisioned by Magruder within an interactive architectural and organic environment that also drew its inspirations from da Vinci's "Vitruvian Man."

Commissioned for Turbulence.org (http://transition.turbulence.org/Works/vitruvianworld/), The Vitruvian World allows real-life users in art galleries interact with Second Life avatars logging on from anywhere in the world, and a third, ghostly, presence: an ever-present, all-seeing "doll" whose aerial perception of the Vitruvian World is constantly streamed back into the world as semi-translucent "memory textures" overlaying the architecture and activity down below. It is at once a place and a site of shifting perceptions, and cultural locations, between the very ancient and the very contemporary, the historical and the artistic, the visual and the experiential.

My final example arises out of the meeting between my own, decades-long engagement with the person and work of a Swiss theatre director, designer and theorist and pioneer of modern theatre, Adolphe Appia, about whom I have published several books, and the mixed realities through which we now increasingly refract our experience of the historical.

In the early twentieth century, Appia sought to develop configurations of space, time and movement that would create a "living'" environment for performances, comprised of our now familiar expressive elements of space, movement, visualisation, sound, time, and the human body.

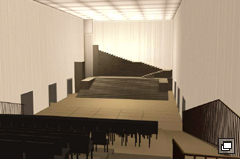

Visualisation of the Great Hall, Hellerau, with Appia's 1912 design for the Descent of Orpheus into the Underworld. Model by Drew Baker. © King's College London 2009

With the aid of funding from the AHRC, the KVL team investigated Appia's visionary, scenographic studies, which he called "rhythmic spaces", as well as the designs that he created and actually realised in the celebrated eurhythmic performances, with Jaques Dalcroze, at the garden city of Hellerau in the now renowned 1912 and 1913 seasons, to which the movers and shakers of the European theatre world flocked.

Then, in 2007, we undertook to explore evolutionary extensions of this work through collaboration with Trans Media Akademie, Hellerau with the aim of creating a series of mixed-reality experiences that would extend a historical performance design concept into digital environments and Second Life.

The artwork, conceived by Michael Takeo Magruder, is based upon two of Appia's stage designs, the 1912 "Descent into the Underworld" and "The Staircase" - a rhythmic space from 1909. The modular units out of which the physical stage sets would have been created were researched and individually modelled by Drew Baker, and then scripted to drift, gently, from one scenic configuration to the next in a state of constant flux within the light and wind of the virtual world, responding to real-time input by both avatars and autonomous algorithms, and creating a living space for performance that reacts to, but is not wholly dictated by human intention.

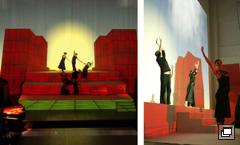

Rhythmic Space(s), mixed reality performance at Hellerau by M. Takeo Magruder, KVL, et al. © Takeo/KCL 2007

Finally, at the CyNetArt07 festival in November 2007, this virtual, living scenographic sculpture was projected at life-size into the Great Hall in Hellerau itself, as a kind of ephemeral after-echo, in light, colour and sound, of Appia's staging in the same spot nearly a century earlier, and following in the footsteps of the eurhythmic performers of 1912, both avatars, from the Association for Dance and Performance Telematics, Tokyo led by Yukihiko Yoshida, and physical performers, students of the Carl Maria von Weber Music Academy in Dresden led by Prof. Christine Straumer, created new choreographies made possible both by the historical legacy and their remediation in the mixed reality of Real and Second Life.

Reviewing the performance, Professor Johannes Birringer, commented:

So we were able to see the performance on the very location where the 1912 production of Orpheus was created, except that we are now in the real / renovated historical building with Appia's set and scenography digitally created and projected by Magruder. But rather than using VRML or a game engine, Magruder's 3D digital Rhythmic Space(s) metaversal environment has been transferred to a large SIM in Second Life, and during the presentation he performed some uncanny manoeuvres to transmutate the Bilder (scenes) for the musician-dancers, as he was able to make the Appia 3D sets slowly disintegrate and change into different spaces of scenic-rhythmic lighting. A choreography of light and slow mutation, a mesmerizing thing without name. The exploration here points to the interrelationships between real and virtual worlds, connected through the network and the technologies (positional tracking, motion tracking, etc) that connect physical performance rhythms and motion behaviours of avatars in tele-plateaus and their Second Life versions…

Birringer's assessment might also serve as an apt conclusion to this paper and the ideas I have tried broadly to present:

The performance…provided a unique historical moment whose significance one might not be aware of now - and what the future of such experiments will bring we don't know at this point.

But, one might add, the science of visualisation is one whose luminous future, as it continuously helps us to visualise the continent of our cultural heritage - past and emerging - spreads out before us, extending and challenging our capacity to explore, to learn, to imagine and even to reencounter those "good ghosts" of the past.

Bibliography

Baker, D; Bentkowska-Kafel, A; Denard, H. (eds.) (forthcoming) Paradata: Intellectual Transparency in Historical Visualization (Ashgate)

Barnabei, F. (1901) La Villa Pompeiana di P. Fannio Sinistore Scoperto presso Boscoreale (Rome)

Beacham, R.; Denard, H. (forthcoming) Living Theatre: Roman Theatricalism in the Domestic Sphere (Yale University Press, forthcoming)

Beacham, R. (2006) Adolphe Appia: Kunstler und Visionar des Modernen Theaters (Alexander Verlag)

-- (2007) "'Bearers of the Flame': Music, Dance, Design, and Lighting, Real and Virtual. The Enlightened and Still Luminous Legacies of Hellerau and Dartington" Performance Research Vol.11;4 Digital Resources Issue, 81-94, with CD.

Beacham, R; Denard, H. (2003) "The Pompey Project: Digital Research and Virtual Reconstruction of Rome's First Theatre." Journal of Computers and the Humanities. Vol. 37;1, 129-140.

Beacham, R; Blazeby, M; Denard H. (2005) "Roman Theatre and Frescos: Intermedial Research Through Applied Digital Visualisation Technologies", in Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Virtual Systems and Multimedia, (Archaeolingua), 223-233.

Beacham, R; Denard, H; Niccolucci, F. (2006) "An Introduction to the London Charter", in The e-volution of Information Communication and Technology in Cultural Heritage (Archaeolingua), 263-269.

Beacham, R; Denard, H; (2003) "The Pompey Project: Digital Research and Virtual Reconstruction of Rome's First Theatre" Co-authored with Richard Beacham. Refereed Proceedings of the ACH/ALLC Conference: 'Digital Media and Humanities Research' Journal of Computers and the Humanities Vol.37 No.1, 129-140.

Magruder, M.T. (2007) "Isolation to Population, Microcosm to Environment: The transition from VRML to Second Life as a platform for networked 3D arts practice" in J. Birringer, T.Dumke, K. Nicolai (eds) Die Welt als virtuelles Environment (TMA Hellerau, DE), 100-114.

Magruder, M.T. (2008) "Virtual Me(s): Avatar embodiment in the console age" in G. Boddington, E. Cuisinier, D. Roland (eds), Virtual/Physical Bodies (centre des arts, FR), 34-41.